1994

To a time traveler from the present day, Pride 1994 would look very familiar. The parade followed the current route from Normal Street to Balboa Park and featured many familiar entries. The festival was at the now-familiar site at Marston Point, although it was slightly less crowded than at modern festivals. As for the rally… well, Pride was trying new things in order to increase rally attendance as they continue to do today.<a/p>

To a time traveler from the present day, Pride 1994 would look very familiar. The parade followed the current route from Normal Street to Balboa Park and featured many familiar entries. The festival was at the now-familiar site at Marston Point, although it was slightly less crowded than at modern festivals. As for the rally… well, Pride was trying new things in order to increase rally attendance as they continue to do today.<a/p>

Behind the scenes, a new Executive Director was building on her predecessor’s successes and trying innovative approaches. The Pride staff continued to develop and grow, adding a few fresh faces, like Public Relations Coordinator Frank Sabatini Jr. The Board of Directors remained stable, with many experienced holdovers from previous years and a few fresh faces to boot.

Meanwhile, looming in the background like the ghost of Christmas past come back to haunt Pride, former mayor Roger Hedgecock and his “normal people” were out to make some anti-gay points.

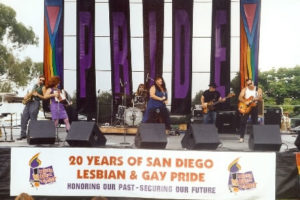

San Diego Pride’s theme that year was “Honoring Our Past, Securing Our Future” and, in many ways, 1994 was all about Pride’s past and its future.

New Executive Director Brenda Schumacher honored the past by building on the foundation set down by her predecessors, but she also took steps to begin a record of the present, so that in the future, we would know our past. In 1994, she began the custom of taking copious photographs of the parade, rally, festival and events behind the scenes so that Pride would always know where it came from and where it has been.

Great care was taken to capture as many photographs as possible and then place them in photo albums in a precise order so that future generations could someday look back and see what Pride was once like. This was an amazingly important step and one that unfortunately wasn’t taken earlier. As this project has learned, too many pieces of our history have been lost over the years; discarded, or forgotten about in an attic, or locked away in “a secure location” that is not easily accessible for casual inspection.

Breaking Up is Hard to Do

When San Diego Lesbian and Gay Pride was formed, originally as the 15/20 committee, it was technically a program of the Center. It operated under the umbrella of the Center for tax purposes and was not its own non-profit (501c3) corporation. In 1994, like a child moving away from home, Pride left the protection of its parent organization to strike out on its own. Both internal and external pressures may have contributed to this decision.

Internally, many former Board members have said that it was simply time for Pride to grow up and leave the nest, and that it had been something the Board had been considering for awhile. Pride had grown large enough, and matured enough, that it was not only self-sufficient, but it was capable of giving back to the community. The Board was securing Pride’s future by making it an independent entity in the community.

While the Pride Board was already planning to chart its own course, a piece of our honored past was making the decision easier.

The “Normal People” Contingent

Former mayor Roger Hedgecock was once known as a friend to Pride and to the community. A moderate Republican, Hedgecock was the first mayor to issue a proclamation for Pride weekend. It was only a proclamation for “Human Rights Day,” but in 1983 it was a big first step. Two years later, he left office after being convicted of one count of conspiracy and 12 counts of perjury regarding improper campaign contributions.

After leaving office, Hedgecock found a home on AM radio and his political leanings took a sharp turn to the right. By 1994, he had gained a sizeable audience with his local talk show and he set his sights on San Diego Lesbian and Gay Pride. At the time, one of conservative radio’s favorite topics was to argue that equal rights for gays and lesbians, were in some way “special rights” demanded by a minority. As part of his anti-gay crusade, Hedgecock and some of his listeners decided that they wanted to march in the Pride parade as a “Normal People” contingent.

Pride refused to let an anti-gay contingent march in the parade, so Hedgecock took the matter to court. Part of his argument was that Pride was a part of the Center and that since the Center accepted public funding, it could not legally discriminate against his contingent. The former mayor and his listeners eventually lost their court case, but it may have contributed to Pride’s decision to separate from the Center at that time.

The Main Event

With the court case behind them and out on their own for the first time, Pride focused on putting together their biggest event so far. An estimated 60,000 people attended the various events over the weekend. San Diego was becoming a big deal.

The parade began to look like the modern parades of today. Familiar names like Rich’s, Mama’s Kitchen, and Metropolitan Community Church went all out on elaborate floats and vehicles to show their pride. Marching contingents were also abundant including a police officer contingent.

The presence of police officers marching in the Pride parade was amazing. Ten years earlier the police were barely tolerant of homosexuals and they were largely unwilling to work with Lambda Pride to keep the peace in the years when the fundies were out in force. Twenty years earlier, the police routinely raided gay bars and harassed gays and lesbians with relative impunity.

The rally was moved to Friday night in front of the Center on Normal Street. Award recipients and speakers included Chris Kehoe, Vertez Burks, Scott Fulkerson, Larry Baza, and Nicole Ramirez-Murray. The Keynote speaker was Morris Kight, one of the godfathers of the Pride movement on the west coast, and someone who had helped advise the San Diego Pride movement since the days of the Gay Liberation Front.

The festival continued to grow in size and attendance as word began to spread about the festival’s prime location in Balboa Park. Entertainment included The Flirtations, Bronski Beat, Lea Delaria and local favorite Candye Kane. The Lesbian Health Fair and The Children’s Garden, both introduced the previous year, continued to grow and the Imperial Court presented a Drag Historical Archives exhibit.